QUBIC BLOG POST

Beyond Binary: Ternary Dynamics as a Model of Living Intelligence

Written by

Qubic Scientific Team

Published:

Jan 27, 2026

Listen to this blog post

The brain is dynamic and non-binary

Biological brain networks do not operate as a decision switch between activation and rest. In living systems, inactivity itself implies dynamism. Absolute “rest” would be incompatible with life. As we saw in the first chapter, life unfolds in time.

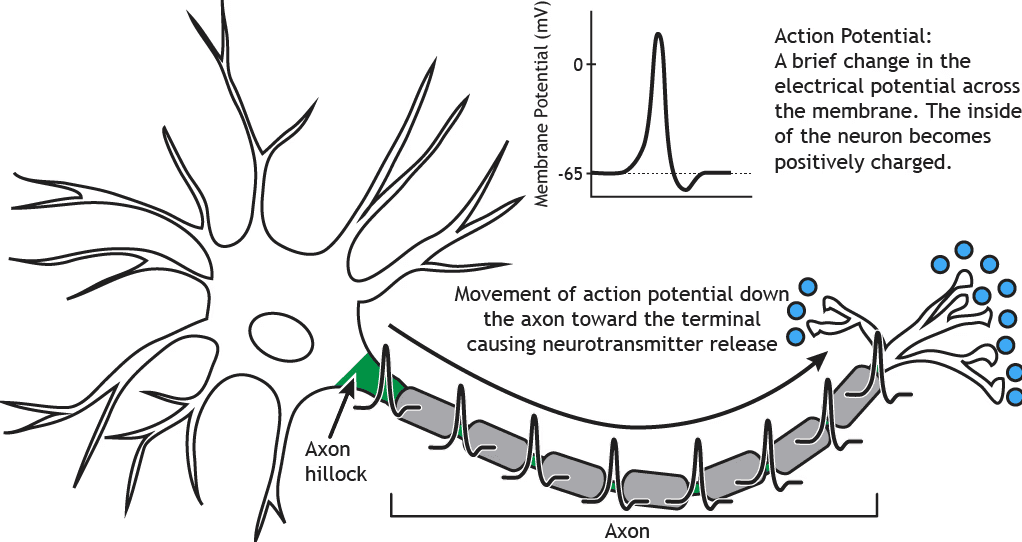

An individual neuron may appear as an all-or-nothing event, transmitting electrical current to another neuron in order to inhibit or excite it. However, prior to that transmission, the action potential, the neuron continuously receives positive and negative inputs in a region called the dendrites. If the global sum of these inputs exceeds a certain threshold, a physical conformational change occurs, and the electrical current propagates along the axon toward the next neuron. For most of the time, neuronal processing takes place below the action threshold, where excitatory and inhibitory currents are continuously integrated.

In computational neuroscience, it is well established that the brain is a continuous dynamic system whose states evolve even in the absence of external stimuli (Deco et al., 2009; Northoff, 2018).

There are no discrete events or resets in the brain. Each external stimulus acts upon a living system that already has a prior configuration. A stimulus may bias an excitatory or inhibitory state, but never a static one. It is like a ball on a football field: the same trajectory triggers different outcomes depending on the dynamic positions of the players. With an identical path, the play may fail or become a decisive assist.

The mechanisms that keep neurons active independently of immediate stimuli are well known.

One of them consists of subthreshold inputs, which alter the membrane potential without generating an action potential.

Others include silent synapses and dendritic spines, which preserve latent connectivity between neurons or promote local activation.

The most important mechanism involves metabotropic receptors linked to neurotransmitters, which organize context. They don't directly determine whether an action potential is triggered. Instead, they define what is relevant or not, what reward prediction a stimulus carries, what level of alert or danger is present, how much novelty exists in the system, what degree of sustained attention is required, what balance between exploration and exploitation is appropriate, what should be encoded versus forgotten, how the internal state is regulated, and when impulse control or temporal stability is advantageous.

In other words, metabotropic receptors implement a form of wise metacontrol. They are not data, but parameters! They function as dynamic variables that adjust system behavior. They allow the system to become sensitive to the functional meaning of a situation (novelty, relevance, reward, or threat) without requiring immediate responses.

Returning to the football metaphor, metabotropic receptors correspond to team tactics: deciding when to attack or defend, that is, deciding how the game is played.

From a computational perspective, these mechanisms operate through intermediate states. They are not binary (active/inactive). The system operates in three modes: excitatory, inhibitory, and an intermediate state that produces no immediate output but modulates future dynamics.

When we speak of ternary in biological brain networks, we are not referring to a mathematical abstraction or calculus but to a literal functional description of how the brain maintains balance over time.

For this reason, computational neuroscience does not primarily study input–output mappings, but rather how states reorganize continuously. These states are fundamentally predictive in nature (Friston, 2010; Deco et al., 2009).

LLMs are binary computations.

In large language models, the concept of ternarity does not make sense. Learning is fundamentally based on error backpropagation. That is, once the magnitude of the error relative to the expected data is known, an optimization algorithm adjusts parameters using an external signal.

How does this work? The model produces an output, for example the prediction of the most likely next word: “Paris is the capital of …”. If the response is Finland, this is compared with the correct word from the training set (France). From this comparison, a numerical error is computed. This error quantifies how far the prediction deviates from the expected value. The error is then transformed into a gradient, namely a mathematical signal that indicates in which direction and by how much the model’s parameters should be adjusted to reduce the error. The weights are updated backward only after the output has been produced and evaluated.

The error is computed a posteriori, the weights are adjusted so that the correct response becomes France, and the system resumes operation as if nothing had happened.

In large language models, the separation between dynamics and learning is especially pronounced. During inference, parameters remain fixed; there is no online plasticity, no habituation, no fatigue, and no time-dependent adaptation. The system does not change by being active.

In the football metaphor, LLMs resemble a coach who reviews mistakes after the match and adjusts tactics for the next one. But during the match itself, the team plays the full ninety minutes without any possibility of technical or tactical modification!

There is pre-match strategy and post-match correction, but no dynamism during play!

LLMs are therefore not ternary in a functional sense. They are matrices of “attention” (transformers) trained offline (Vaswani et al., 2017). This is not a quantitative limitation but an ontological difference.

Neuraxon and Aigarth trinary dynamics

Neuraxon introduces a fundamentally different framework. Its basic unit is not an input–output function, as in LLMs, but an internal continuous state that evolves over time. In Neuraxon, excitation is represented as +1, inhibition as −1, and between these two states there exists a neutral range represented by 0.

At each moment, the system integrates the influence of current inputs, recent history, and internal mechanisms in order to generate a discrete trinomial output (excitation, inhibition, or neutrality).

The relationship between time and ternary is central. The neutral state does not represent the absence of computation or inactivity but a subthreshold phase in which the system accumulates influence without producing immediate output. It is comparable to a dynamic tactical shift in a football team, regardless of whether it leads to a goal for or against.

Aigarth expresses the same logic at a structural level. Not only are the units themselves ternary, but the network can grow, reorganize, or collapse depending on its utility, introducing an evolutionary dimension that reinforces continuous adaptation. The Neuraxon–Aigarth combination (micro–macro) gives rise to computational tissues capable of remaining active (intelligence tissue units), something impossible for architectures based exclusively on backpropagation.

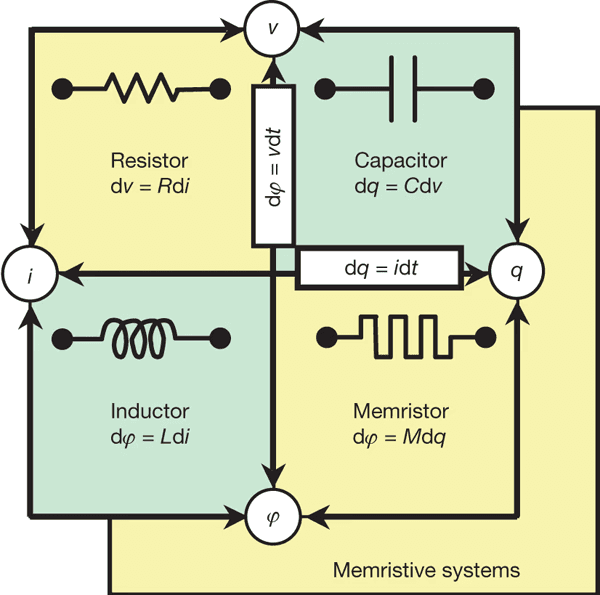

The hardware question cannot be ignored. At present, there is no general-purpose ternary hardware, but there are active research lines in ternary logic, including multivalued memristors and neuromorphic computation based on resistive or spintronic devices (Yang et al., 2013; Indiveri & Liu, 2015). These approaches aim to reduce energy consumption and, more importantly, to achieve ternary computation aligned with physical, living, and continuous dynamics.

Does a ternary architecture make sense even without dedicated ternary hardware? Despite this limitation, it does, because architecture precedes physical substrate. By designing ternary systems, we reveal the inability of binary logic to reflect a dynamic world. At the same time, ternary architectures such as Neuraxon–Aigarth can already yield improvements on existing binary hardware by reducing unnecessary activity.

References

Deco, G., Jirsa, V. K., Robinson, P. A., Breakspear, M., & Friston, K. J. (2009). The dynamic brain: From spiking neurons to neural masses and cortical fields. PLoS Computational Biology, 5(8), e1000092.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

Indiveri, G., & Liu, S.-C. (2015). Memory and information processing in neuromorphic systems. Proceedings of the IEEE, 103(8), 1379–1397.

Northoff, G. (2018). The spontaneous brain: From the mind–body problem to a neurophenomenology. MIT Press.

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., et al. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30.

Yang, J. J., Strukov, D. B., & Stewart, D. R. (2013). Memristive devices for computing. Nature Nanotechnology, 8(1), 13–24.