QUBIC BLOG POST

Analysis of Benchmarking World Model Learning

Written by

Qubic Scientific Team

Published:

Jan 13, 2026

Listen to this blog post

You walk through your city while having a conversation with a friend. Your nervous system is constantly estimating variables: your bodily position, the speed at which you move, direction, the structure of the environment, and the expected margin of error in your movement. These variables are not recalculated from scratch at every step; they are updated continuously. If someone suddenly crosses your path or the ground changes, this new information does not cancel the previous state but adjusts it. We can keep walking because our internal model preserves temporal coherence. If we enter a less familiar street, the system adapts without losing continuity. In cognitive neuroscience, we call a world model this capacity to sustain a stable, correctable, and anticipatory internal dynamic. It is not a map of the environment, but rather an implicit system of equations that links perception, action, and time.

Another simple example is cooking. It is enough to listen to the sound, observe the steam, and know how long the pot has been on the stove to know that the eggs are cooked. There is no need to open the pot. If you do it the next day in a different kitchen, you do not get lost. The knives may be in a different drawer, but your internal world model adjusts quickly. It is evident that the brain does not create a map of each kitchen, because that would require a map for every place, but instead builds an operational understanding of how things work.

To achieve this, it maintains an internal state that evolves over time. It does not wait passively for something to happen in order to react, but continuously anticipates. When something does not occur as expected, the error does not erase the model; it adjusts it.

When we talk about "world models," both in the brain and in artificial intelligence, we are not referring to static representations or explicit descriptions of reality. It is the capacity of a system to maintain an internal state that evolves over time and allows it to anticipate, correct, and act without continuously resetting.

In artificial intelligence, the concept of a world model is similar. A system with a world model does not merely respond well to immediate stimuli; it has learned the dynamics present in the environment. It can simulate what will happen next, what would happen if something changed, and how to reorganize its behavior when conditions are no longer the usual ones. For many researchers, real progress in AI implies learning world models.

Previous Approaches to World Models

In the past, approaches to world models have been evaluated indirectly. In reinforcement learning, for example, agents are measured by the reward they obtain. An agent may learn that a particular stove burner "works better" because it yields more reward, but that does not imply that it has truly learned why. It can function without having a world model in the strong sense.

In other approaches, such as the ARC Challenge, the evaluation focuses on whether a system can infer hidden rules from examples. For instance, if the rule consists of a static geometric relationship in which certain figures are contained within others and that relationship is preserved in new cases, the system adapts. However, it fails if the figure changes size. It operates in static environments, without exploration or interaction.

The WorldTest Framework

The article Benchmarking World Model Learning starts from this limitation and points out that it is not enough to measure whether a system predicts well or solves a task. If we want to know whether it has learned a world model, we have to ask directly.

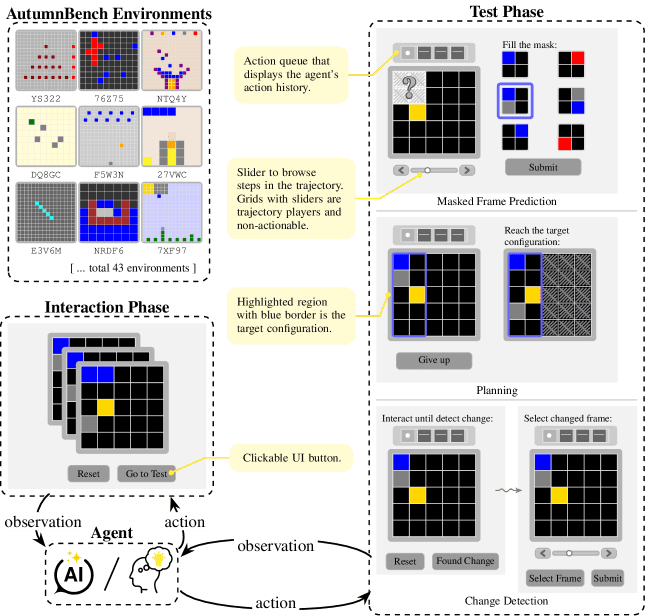

The authors propose a new framework, WorldTest. The idea is simple. First, the agent interacts freely with an environment without receiving external rewards. Then, it is confronted with a new challenge derived from the original environment, with an explicit objective that is different but related. Performance in this second environment reveals what the agent has truly learned about the world, not just which actions maximized a previous reward.

To this end, they present a set of grid-world environments with three types of challenges that reflect very basic human capacities.

Figure 1:Overview of the WorldTest framework and the AutumnBench instantiation. Agents first interact with an environment without external rewards to build a world model, then are evaluated on a derived challenge. Top-left box shows the 9 example AutumnBench environments. Yellow notes in the middle explain the key UI elements in the human interface of AutumnBench.

World Test framework examples. From Warrier et al. 2025.

The first consists of predicting unobserved parts of a final trajectory, such as when we infer how much time remains for a meal to finish cooking without seeing it, or when, while walking through a city, we know how far we are from a familiar square based on the distance traveled and partial environmental cues.

The second requires detecting changes in the dynamics of the environment and identifying when something stops behaving as expected, similar to realizing that a new kitchen works differently, or noticing that a familiar street has changed due to construction or traffic closures, and thus recognizing the precise moment when the environment no longer matches the previous model.

The third evaluates planning: how learned information is used to reach a goal, such as organizing a recipe step by step, or choosing and adjusting a route while moving through the city. Decisions are made based on an internal state that is updated with each detour, crossing, or correction of the path.

Why AI Models Fail

The results reported in the paper are revealing. AI models fail, not because they do not "reason," but because they do not properly update their data when contradictory information appears, applying learned rules even when the data no longer fits.

In addition, they do not use neutral actions—such as resetting an environment or doing nothing—as experimental tools. These failures are not so much about memory or reasoning, but about metacognition: how we know what we know, that is, what information to seek, when to doubt, and when to revise what has been learned.

From this perspective, it becomes easy to understand why large language models, such as Claude, Gemini, or Grok, fail these tests. We know they are extraordinary at generating coherent text and fluent responses. They seem to understand. But their internal state is not such a state. There are no variables that evolve over time according to their own dynamics.

Returning to our examples, we know that an LLM can explain how a kitchen works, describe what would happen if we changed a pan, and perfectly explain an action plan for a recipe. But it cannot detect that its world model is failing.

WorldTest shows that they fail in temporal stability, in dynamic generalization, and in simulating a reality that differs from the data.

Neuraxon's Approach

In Neuraxon, we treat time as part of the system's state. Internal variables exist, persist, evolve, and change through explicit dynamics. The system does not "remember" the world; it keeps it active.

From the perspective of the benchmark described in the paper, this enables something that LLMs cannot offer: adapting structure when the rules change. It is not a matter of more data, more parameters, or more computation.

Ultimately, not every system that predicts well has a world model. The brain does. We verify this every day in tasks as simple as cooking or moving through a familiar space. If artificial intelligence aspires to something more, it must include world models and therefore rethink its architecture, rather than merely scaling its existing scheme with power and money. For Neuraxon–Qubic–Aigarth, the architecture is dynamic and therefore capable of real-time adaptation.

Decentralized Infrastructure for World Models

Considering the current status of the world-model AI system, it's crystal clear why decentralized computational infrastructure becomes relevant. Qubic architecture, decentralized design and with uPoW mechanism provides a computational substrate where computation is ongoing rather than episodic. In Qubic a decentralized architecture is not just a scalable platform, but an enabler of a fundamentally different class of intelligent systems grounded in real time rather than reconstructed on previous fixed data sets.

References:

Warrier, A., Nguyen, D., Naim, M., Jain, M., Liang, Y., Schroeder, K., & Tavares, Z. (2025). Benchmarking World-Model Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.19788.

Related reading: Learn more about Qubic's AI infrastructure and how uPoW enables decentralized computation.